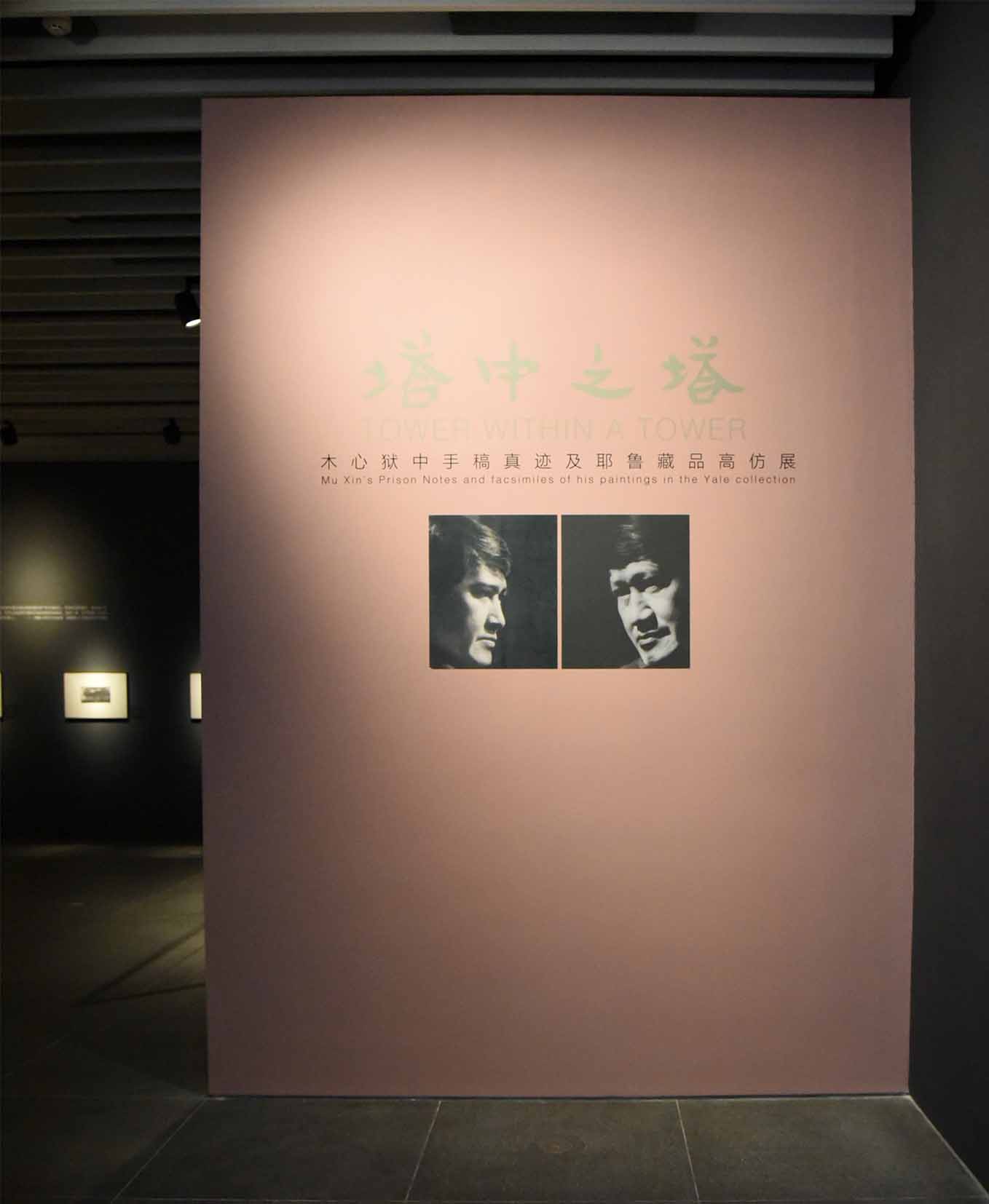

Duration: 15th Oct 2017-20th June 2018

B1F, Temporary Gallery 1.

In 1977, the Cultural Revolution had just ended, and the reform had not begun. Mu Xin was no longer under an illegal house arrest, but served a labour sentence until his official rehabilitation in 1979. For three years, every day after work, he drew the curtains in his apartment in Shanghai, and secretly began painting again; he had not been able to paint in nearly a decade. Later he said of these years:

A slave during the day. A prince at night.

Twenty-two years later, these paintings and Mu Xin’s Prison Notes from 1974 were exhibited at Yale University Art Gallery. Mu Xin’s own words were quoted in a review article in the New York Times.

Four decades ago, Mu Xin, aged fifty, made fifty paintings in memory of his tormented years bygone. A dozen or so were an audacious extension of the influence of Lin Fengmian’s ink colours; thirty-three small-scale landscapes were his experimentation, commenced in the 1960s, with transfer painting. The Cultural Revolution had brought his dreams to a halt. Now he could relive, through transformed traces of ink and water, memories of the great Song and Yuan landscape tradition; combined freely with imagination of his hometown, his highly individualistic techniques and style went beyond the framework of his teacher.

One day in 1979, to a small group of ‘underground’ artists in Shanghai, Mu Xin showed his fifty works. The art world having at the time been deprived of outside information for a decade, even Lin Fengmian’s early modernist style was prohibited and forgotten, let alone Mu Xin’s unexpected experiments. The painter Chen Juyuan, who was present, recalls the event which left the entire audience speechless. The ‘prince’ himself, who had hoped for resonance, was likewise lost for words. Afterwardshe went alone for a drink, and got drunk.

In the three months that followed, Mu Xin was again in hiding. Chen Juyuan did not overlook this episode. Upon reflection, he sent Mu Xin a letter with considered compliments. Mu Xin’s grateful response soon arrived; written with a brush in both classical and vernacular Chinese, his letter totaled eight pages. After all the turmoil he had endured, this was the first time that he received praise, which came from one sole person. It was also his only ‘solo exhibition’ ever held in mainland China.

In 1982 Mu Xin moved to New York. Twenty-seven years later, in 2009, Chen Juyuan visited him in Wuzhen. Mu Xin, who had returned to his country, died two years later. In 2015, Chen Juyuan attended the opening of the Mu Xin Art Museum. This year he donated the letter, which he had treasured for forty years, to the Museum.

In the twenty-four years that he lived in New York, Mu Xin sold some of his fifty works; the thirty-three small transfer paintings stayed with him. In 1985, Wu Hung, then a PhD candidate, organised an exhibition of these works at Adams House at Harvard University. Richard M. Barnhart, professor of art history at Princeton University, applauded Mu Xin’s ‘landscape painting at the end of time’. In the early 1990s, through the recommendation of the artist Liu Dan, Alexandra Munroe (then director of the Japan Society Gallery and presently Senior Curator of Asian Art at the Guggenheim Museum, New York) began gestating an exhibition of Mu Xin’s thirty-three transfer paintings and sixty-six pages of Prison Notes. In 1995, the collector Robert Rosenkranz purchased these paintings; in 2001, he donated them all to Yale University Art Gallery.

In the same year, Yale University Art Gallery held ‘Art of Mu Xin’, which travelled thereafter to the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, Honolulu Academy of Arts, and the Asia Society in New York, where the title of the exhibition became ‘Landscape of Memory: The Art of Mu Xin’. These four exhibitions received fourteen reviews in the United States. The accompanying catalogue of the Yale exhibition was judged as a five-star publication.

As readers know, in New York Mu Xin resumed writing, and published a dozen or so volumes. In the new century, Mu Xin, in his seventies, started producing transfer paintings again, his style transforming several times over, and continued painting until the age of eighty-three, a year before his death. His works, one hundred and seventy pieces in all, are now in the collection of the Mu Xin Art Museum.

After discussion, in the spring of 2017 the Yale University Art Gallery gave the digital version of Mu Xin’s thirty-three transfer paintings to the Mu Xin Art Museum, as well as the authorisation to make facsimiles of these works to be displayed alongside Mu Xin’s original Prison Notes. So it is that today, in Mu Xin’s country and hometown, his Yale exhibition of seventeen years ago is recreated. For the Yale exhibition, Mu Xin had envisaged, with a poet’s wit and honesty toward history, ‘Tower within a Tower’ as its title, one which summed up his seventy years of struggle through painting and writing. Because the meaning of its English translation might not be immediately apparent, this title was not used. It is, however, the title of this current exhibition. Here is Mu Xin’s own elucidation:

The first tower refers to the Tower of London, an analogy of actual circumstances. The second refers to an ivory tower, ironic in nature. It thus reads: ‘An ivory tower within the Tower of London’. After the May Fourth Movement, an ‘ivory tower’ was routinely deployed in artistic and literary debates by the supporters of ‘Crossroads’ [a 1937 movie] to denounce the opposite camp. I have nothing to do with either camp. What I am saying is this: whilst imprisoned in the Tower of London, I sculpted an ivory tower.

Alluding to the Tower of London, historically a prison, to speak obliquely of his own experience, and declaring openly an Ivory Tower as his clear-headed artistic pursuit defying political dictates -- this is Mu Xin. Throughout years of despair, these small paintings and manuscripts were his salvation; they were his only joy. It was impossible for them to be shown at the time they were produced; indeed they were never meant to be seen: they were a ‘tower within a tower’. One could hardly find a comparable image or metaphor in the histories of Chinese painting and literature. At the opening of the Yale exhibition, out of an obstinate desire to hide, Mu Xin was absent. Today this exhibition opens in his hometown, and he is still in hiding, in a place we cannot find.

Chen Danqing